The Cost of Oil in Tunisia’s Desert

In recent years, Tunisia’s natural hydrocarbon resources has been a topic of heated debate, despite a lack of transparency from authorities and private companies alike.

In some cases, the State waives its ownership rights of these resources to foreign companies and then purchases the extracted gas back to meet domestic consumption needs, seemingly at a loss to public coffers. Others have seen the issue as a problem of regional inequality: oil- and gas-rich interior regions not receiving the profits returned back as reinvestment. In that vein, there have been some attempts to understand social movements and protests around the oil and gas sector as a popular redefinition of the development model.

But there’s also local environmental and health issues at stake. Meshkal went to Tataouine governorate this January and listened to numerous testimonies and reviewed video evidence indicating that hazardous waste produced as a byproduct from oil and gas extraction in the desert has been either dumped directly into the ground or done without proper chemical treatment and in overfull pits, in violation of regulations and in the absence of official oversight mechanisms to enforce regulations. Meshkal could not verify whether the problem is systematic or occasional as the problem is largely out of sight, far out in the desert in areas designated as military zones which cannot be entered without special permits. But when Meshkal sought comment from the Ministry of Environment’s National Agency for Environmental Protection (ANPE by its French acronym), they too said they have trouble getting permits to conduct field visits, and they rely on the oil companies they are supposed to regulate to facilitate their oversight visits as they lack the equipment to do so.

Activists told Meshkal that they have seen environmental and health impacts that they believe are a result of untreated waste dumping. This includes affecting the health and welfare of residents in nearby areas, including especially camel herders whose livelihoods depend on the desert’s scant water resources. Locals also say they have noticed health problems in birds. Experts say there are also unseen environmental impacts, such as pollution of the water table.

Most of those interviewed by Meshkal requested anonymity as they said they fear for their own safety and the safety of family members, noting that those activists that have spoken out and especially those who participated in the Kamour protest movement have faced arrest and violent repression from authorities. A company manager and two out of three State officials we spoke with requested anonymity as they were not authorized to speak to the press. Activists also said they face reprisal from potential employers as the oil and gas industry is the most lucrative industry in a region that suffers extremely high unemployment.

The Kamour movement began in April 2017, when demonstrators launched a sit-in at the Kamour oil and gas pumping station in Tataouine’s desert demanding State investment and employment. Demonstrators called for development and for the region to benefit from oil and natural gas revenues. While they won concessions from authorities in the form of a signed agreement, the government has so far not followed through on most of its promises in the agreement, prompting continued protests. The anti-corruption and transparency association IWatch launched a project in 2020 called “Kamour Meter” which measures how many of the agreement’s promises the government has fulfilled: 33 percent at launch, which has not increased since the meter was launched. Still, activists say the Kamour movement has reinvigorated attempts to get more transparency around oil sector issues.

Dumping Sludge Directly into the Ground

In the extraction of oil and gas, there is a waste byproduct, a sort of sludge or mud that specialists described to Meshkal as ground soil contaminated by oil and chemicals that were introduced in the extraction process. Tunisia employs a method of treating this waste called SS, or “solidification and stabilization.” A short guide to this process produced by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) describes the technique as follows: “Solidification binds the waste in a solid block of material and traps it in place….Stabilization causes a chemical reaction that makes contaminants less likely to be leached into the environment.” The EPA notes that this is a relatively low-cost method to deal with contaminants, and a Tunisian engineer specialized in the subject explained to Meshkal that many other countries use a newer technique called thermal desorption.

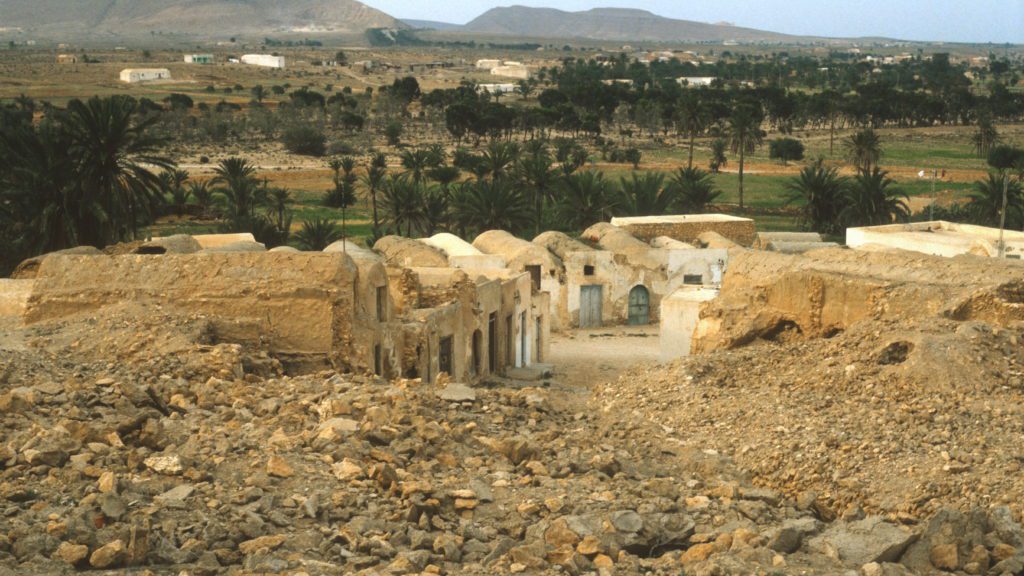

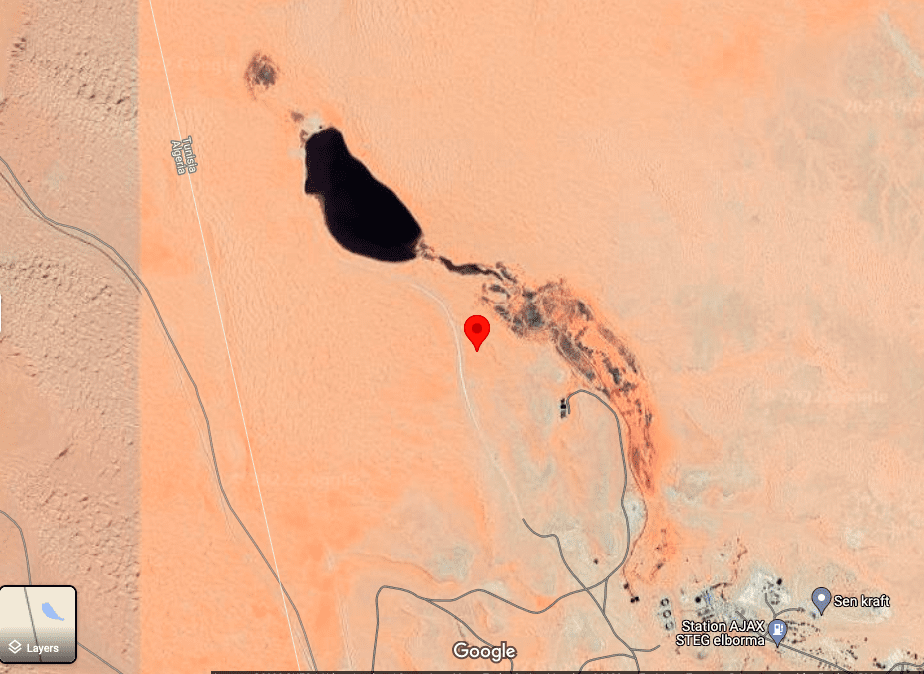

But several activists, engineers, and others working in the sector told Meshkal that waste from oil and gas extraction sites in the desert of Tataouine governorate is sometimes not treated at all. Most of Tunisia’s onshore oil and gas fields are located in Tataouine governorate, home to a few small cities including Tataouine city. One stunning example can be seen from space, available on Google Maps’ satellite imagery: a black lake of sludge outside the petroleum drilling field in Al Borma, near the Algerian border. According to multiple experts Meshkal met in Tataouine, that sludge lake has existed since the 1970s and it’s full of contaminated water that is the waste from oil drilling operations. Also visible in satellite view are the pipes that connect the drilling field to the lake.

“Those remains are supposed to be in a closed container, but as you can see they are floating,” said Rami (not his real name), an expert who said he is hired as a freelance consultant to fill out bogus compliance forms on behalf of waste management companies which are submitted to the oil companies that contract them.

One ANPE official who requested anonymity and Yassine Marzouki, head of studies at ANPE, told Meshkal in an interview at the ANPE headquarters in Tunis on February 16, 2022 that they were planning to do a field visit to Al Borma, but that they have not been able to due to a lack of resources. They said that ANPE has 24 cars, the newest of which is 11 years old, and these cars are not in condition to make desert trips; so they rely on the oil companies they are supposed to oversee to help them make such visits. The ANPE officials also told Meshkal that they have trouble getting authorization from other branches of the government to visit desert areas, which were designated as military zones in 2012. However article 8 of decree 2273 from 1990 gives the ANPE’s inspectors “access to all public and private establishments” which they are tasked with monitoring. The officials said that in practice they are limited to writing up reports on infractions and referring them to prosecutors (article 12 from law 91 in 1988 which established the ANPE confirms as much).

The ANPE is under the Ministry of Environment. In 2020, the former Minister of Environment and 22 other officials were arrested as part of a corruption scandal involving waste management and the Ministry of Environment’s National Agency for Waste Management which had imported household waste from Italy.

A 2013 article indicates that the Al Borma field still has Tunisia’s largest recoverable oil reserves with 750 million barrels at the time. The concession for the Al Borma field, according to the Tunisian National Oil Company (ETAP)’s website, is 100 percent under SITEP (Italian Tunisian Petroleum Exploitation Company).

While the Al Borma sludge lake dates to the 1970s, there seem to be more recent violations underway. Meshkal reviewed two videos shown by activist Chawki (not his real name) that appear to show sludge being dumped directly into an open pit, without any sealant or container. According to Chawki, who is also a member of the Kamour movement’s negotiation committee, the video dates to 2018 and was taken on cell phones by workers for a waste management company who were working inside a petroleum drilling field. Chawki said he and fellow activists acquired the videos when the workers gave them to them.

Chawki said they tried to get national media interested in the videos, and a popular investigative TV journalism program was initially interested but ended up not covering the issue. As for the workers, Chawki claims they were subsequently fired, but Meshkal was unable to verify this or contact any of the workers involved in making the videos.

Chawki said that the direct dumping into the ground as seen in the video is in violation of the State’s public procurement protocols [listed in a cahier de charge] which stipulate proper treatment methods. Chawki said they have had trouble finding a copy of the protocols, which ought to be public but are not always easily accessible.

Waste “Treatment” Way Below Cost

But not all the issues with waste management are as blatant as direct dumping into the earth. There is also a lot of corner cutting, according to people working in the sector. There are three major waste management companies that are operating in Tataouine as subcontractors to petroleum companies: New Eau Ster Petroleum Services, Golden Petroleum Services and Hasna Petroleum Services. All of the allegations of improper waste treatment that Meshkal heard referred to only two of these three companies. One official from the State’s ANPE claimed that any allegations of environmental violations were a result of one company trying to tarnish the reputation of the others with false information.

But Badr (not his real name), who works as an engineer in the sector, explained that some companies cut corners by either overfilling waste pits by up to three times their capacity or by filling the waste pits without applying any chemical treatments to neutralize the contaminants within, or by doing both: overfilling and not treating. The real cost of treating this petroleum sludge properly is between 65-70 dinars per cubic meter, according to Badr, not including other costs like labor and equipment. Yet, Badr said there are contracts signed for 30 dinar per cubic meter, and the lowest bidder always wins. To make a profit at that price, corners are cut, and Badr alleged that regulators are aware but are doing nothing.

“There are many pits that haven’t been treated that they covered [anyways]. Why do they cover them at a low cost? Because, in reality, they don’t treat them. Even though they are required to do treatment,” Badr told Meshkal.

Anwar, another local activist, separately told Meshkal a similar account of how companies win bids by offering prices lower than the real cost of treatment and then subsequently cutting corners by misrepresenting the quantity of waste they treat or not treating the waste completely.

“They say: ‘We treated such and such a volume,’ and then, in the end, they dump it in the middle of a condemned pit. In the middle of a pit. Directly into the water table,” Anwar said.

Rami, the compliance consultant, separately also described the cost cutting measures that result in pollution.

“The cost of these waste management operations is very high and, as we are in a country that is filled with corruption, they give you a budget to work with that could barely cover the treatment of household [domestic] waste, let alone hazardous waste,” confirmed Rami, the compliance consultant.

Rami said part of the cost that treatment companies are avoiding is transportation: moving the waste far from the original extraction site.

“Once they start disposing of mud [sludge], it starts flowing outside of the containers straight to the ground…And since the area where they could transfer some of that waste to is 70 kilometers away and transporting it is costly, they pile it up and it becomes like a small mountain,” Rami said.

A third ANPE official speaking to Meshkal on condition of anonymity as he was not authorized to speak to the press denied the allegations. While the official admitted ANPE rarely does site visits, he claimed that if any such violations existed, the ANPE would hear of it from the military and national guard in the area.

Workers’ Health

Rami also said that the workers’ health is put at risk by their work environment when disposing of hazardous waste. He said that to do the job properly, workers need to be highly trained and wear protective equipment, but that employers often hire untrained workers and don’t give them any special protective gear.

“Everything needs to be specialized. However, what’s happening is that the people working on these operations are not trained, do not have the necessary protective gear. They would go into the hole with barely an overall fabric suit and a regular shovel, and they would spend at least half an hour there, exposed to the most dangerous types of gas, namely hydrogen sulfide (H2S), benzene [fumes], carbon dioxide etc.,” Rami said.

Rami also said that workers at waste disposal companies are “getting paid the bare minimum, being cut off from the outside world.”

Company Manager Denies Allegations

However, Meshkal also met with a manager responsible for worker hygiene and safety at one of the waste management companies, Nizar (also not his real name because he is not authorized by his company to speak to the press). Nizar denied Rami’s allegations about worker safety. Nizar told Meshkal that workers at his company are given protective gear and are not exposed to poisonous gas emissions during their work.

“H2S for example is a very flammable gas. If it reaches the surface it would cause explosions and that cannot happen,” Nizar said, adding that workers are given special shoes for working on site.

Nizar also denied ever witnessing hazardous waste being dumped directly into the ground by waste management companies, insisting that big and reputable international companies would not risk cutting corners when the cost of compliance is relatively low for them.

“Of course not all companies respect the law, but big companies do… We receive security and hygiene training before we start working. If you do not abide by the security measures, you get kicked out…And it’s not about the cost. These companies make more than 1 billion dinars per operation. Do you think they would find it a burden to pay 500,000 dinars for waste management?” Nizar added.

Camel Herders Affected

Despite the fact that petroleum fields and waste disposal sites are far from urban areas, some locals still suffer the consequences of improper waste disposal in the Tataouine desert. Among those are farmers in Dhehiba, a town at the border crossing with Libya, south of Tataouine city. Meshkal met with Mustapha Gouider, the president of an independent farmers’ union in Dhehiba, as well as a number of camel herders who said they are affected by pollution.

“We thought that being in the desert made us less exposed to such harm; however, we found ourselves facing random landfills in [the desert’s] heart,” said Gouider.

“There is a lack of [State] oversight in the desert. One of our farmers lost 14 of his camels after they fell into a cesspool… Camels are not like other animals; once they fall and break a leg, they’re doomed to death as they cannot stand up again,” he added.

Gouider described the cesspool as something similar to the big sludge lake at Al Borma—i.e. improperly disposed of hazardous waste produced from drilling operations.

“They use all the water to extract oil, and then they throw the remains straight to the ground,” explained Mohamed Touzni, the camel herder who lost 14 of his camels. Whole camels often sell for over 2000 dinars, more than four times the median monthly household income.

At the same time, local herders claimed that camels as well as local birds are suffering health problems because of the contaminated sludge left by petroleum companies in the middle of the desert. They also said that the only veterinarian in town sometimes sends health samples from diseased camels to the capital Tunis for laboratory analysis at the Ministry of Agriculture, but that they don’t receive responses.

“We come to hate all this waste and life as a whole… No official has visited us since 2010… They are discriminating between us and the companies,” Touzni added.

Exhaustion of Agricultural Water Sources

Herders are not only losing their camels due to pollution. Gouider said oil companies are overexploiting local groundwater that they believe are supposed to be exclusively for agricultural purposes, making it hard for them to supply their camels with drinking water.

“The agricultural wells are being used without any right by these companies… Farmers now are turning into beggars to get what is rightfully theirs… And in addition to that they install a trench limiting the areas where our camels could move,” Gouider said.

In 2016 the state built a trench on the Libyan border ostensibly to deter the movement of jihadist fighters, but herders in Dhehiba say the border has impacted them negatively as camels can no longer cross the borders to look for water and feed in the desert after its installation.

“Water sources belong to the State. The farmer should not become a beggar…These companies must treat [camel] herders well and give them priority,” said Sami Aoun, president of the Dhehiba Environment Protection Association.

“The absence of State oversight is what is causing this…The oversight that is supposed to force them [oil companies] to abide by rules, does not exist,” Aoun added.

Local herders say authorities need to focus instead on curbing the oil sector’s impact on the environment.

“There is a big lack of supervision and an intentional black out…The whole [oil production] sector…it is a black box itself, so of course they will not care about the repercussions. But if this continues, the impact on future generations will be drastic,” added Aoun.

Like experts Meshkal met in Tataouine, Aoun also pointed specifically to a lack of oversight from the Ministry of Environment and its affiliated bodies in Dhehiba.

“There’s not even a real regional representation of ANPE in here,” Aoun said.

The ANPE officials told Meshkal that they have eight representative offices around the country, and the one covering Tataouine is in the Gafsa governorate, which is not adjacent to Tataouine where most of Tunisia’s onshore oil operations take place. Gafsa is about a 400 kilometer drive from Dhehiba.

Lack of Transparency, Oversight

For Chawki, the waste management companies aren’t to blame; it’s the petroleum companies that hire them and officials who are not doing proper oversight that he sees as responsible for pollution.

“These [petroleum] companies have been operating for over 60 years and [officials] do not want to share with us any details about what they’re doing…Whenever you go and start asking questions, they shut their doors on your face,” Chawki said.

A lack of transparency by officials in this sector is not new. In 2014, the head of Parliament’s energy committee was informed of death threats against him after he started exercising oversight over the State’s concessions to foreign petroleum companies.

“We are not able to take a look at any of the specifications that guide these companies’ work,” Chawki said, noting that he also believes that the lack of transparency suggests that corruption is at play. ““I am sure that digging into this will…lead us to [discover more] environmental and health violations.”

Chawki would like to see more direct government oversight over oil and gas operations in the Tataouine desert to ensure that violations of environmental and health norms are recorded and prosecuted.

Desert As Military Zone

Exacerbating the lack of transparency is the fact that no one can enter the zones without a special authorization from the government, what is called a “desert card.” In June 2012, the Ministry of Defense announced that the Tunisian desert was an exclusive military zone and that entering it would require special desert cards.

But even getting a desert card allows one to visit only one specific area of the desert, so it’s difficult for anyone to piece together a full picture of the health, safety or environmental violations that may be taking place. ANPE officials told Meshkal that even they face challenges getting such cards to do their own inspections.

“In the desert, everyone is in a limited zone and can’t travel to another zone…One has to work directly on site to get…information,” said Anwar the local activist.

“It is impossible for anyone who does not work in the desert to have access to it. Even those who work there have specific areas they can enter,” confirmed Rami the compliance consultant.

Locals say the closed military zones and desert card system has exacerbated the lack of information. Moreover, activists say that any concerns or inquiries about environmental violations are shut down by officials who use the military zone as an excuse to evade such questions.

“We want them to open the desert for experts to take a look, let us in… I am sure that those experts will discover the disaster…This is not the [domestic] waste of Italy which they could burn,” Chawki said, referring to a highly publicized case of corruption that saw the former Environment Minister sacked and jailed. “You need to assume responsibility,” Chawki added.

The desert card procedures also gives employers greater leverage over workers who need desert access to get jobs, according to Rami the compliance consultant.

“The fact that you enter the desert, it means that you are under supervision from the company itself,” Rami said.

Rami explained that work in the desert is the only source of employment for many in Tataouine and, for that reason, it becomes hard to find people who are willing to talk. Rami explained this is one reason he requested anonymity to speak to Meshkal. Rami recalled one incident where he publicly denounced what he saw as an improper work procedure on social media and he subsequently lost access to a certain area in the desert.

This article was originally published in Meshkal the 17th of February 2022.