Morocco’s drought-flood chaos fuels a storm of cloud seeding conspiracies.

In the tiny village of Ouneine, nestled high in Morocco’s Middle Atlas Mountains, the sky is everything – a roof, a god, a broker of fortune. For generations, villagers have read the clouds like omens: dark belly, a shifting wind, the scent of damp soil. All signs that rain, finally, might fall.

But in recent years, the sky has kept its secrets. The rain has grown unpredictable, teasing in October, vanishing in March, then returning in furious torrents that carve ravines through parched earth.

On a Tuesday in early September 2024, just days after a week of bone-dry sun, a rain not seen in years swept through the Atlas Mountains, which form the spine of northwest Africa, separating the Sahara from the sea.

On a narrow pass near the road heading to Marrakech, cars came to a halt, their tires trembling on the edge of an abyss amid an unexpected downpour. Drivers stepped out cautiously, picked through rubble with bare hands and stacked rocks to forge a path through a landslide, all while murmuring quiet prayers.

“This isn’t natural,” whispered Hassan, a local taxi driver. His passengers, a group of villagers huddled in the backseat, nodded or prayed for forgiveness. “They say they’re playing with the clouds now. Trying to make rain, instead of leaving it to God,” he added.

In Morocco, rain is never just rain, it is a divine mood made manifest, a conversation between the heavens and the people. In past years, whenever winter came dry, King Mohammed VI, Amir al-Mu’minin, Commander of the Faithful, summoned prayer. Salat al-Istisqa, the prayer for rain, is a ritual pulled from the heart of prophetic tradition.

Worshippers, often barefoot, gather in open fields or mosque courtyards, their garments loose, praying for forgiveness and good. In rural areas, sometimes entire villages march together at dawn, with children leading the way, a reminder that innocence might draw divine mercy.

Elsewhere, in the rugged Amazigh communities of the Atlas, girls still perform Taghanja, an ancient rain rite older than Islam. Dressed in leaves, they parade through their villages, singing to the sky, while elders pour water over their heads in a symbolic invitation to the heavens. In such rituals, drought is not a scientific phenomenon but a test of collective spirit.

“Rain is not just weather for us. It is baraka (a blessing). It comes when the earth is ready and the people are humble,” Aicha, an elder from a valley near Ouarzazate, told AMWAJ.

It was in that village that I first began to understand what cloud seeding and what clouds themselves represent to communities so deeply rooted in the land. The Amazigh New Year, after all, begins with the agricultural calendar. Here, rain is not just water from the sky; it is a sign, a covenant.

But layered over this spiritual connection is a gnawing mistrust, one shaped not by weather patterns, but by politics.

Many in these remote mountain areas speak of government officials not as civil servants but as distant figures from Rabat – “Rabat’s people,” they call them. Men in suits whose names appear in headlines, whose policies shape lives from afar. In these places, where officials rarely, if ever, visit, they turn into mythical creatures whose words and decisions drift in like rumours. Their promises, to many here, feel as intangible as the clouds themselves.

Morocco’s long struggles with drought, and now floods

Morocco has been gripped by its worst drought in decades. For six consecutive years, the kingdom’s skies have offered little more than dust. Rainfall fell below seasonal averages by as much as 67%. The great reservoirs of Bin el Ouidane and Al Massira shrank into cracked basins, exposing old stones and sun-bleached fish skeletons. By 2023, the country’s dam-filling rate dipped below 30%, and in some southern provinces, water had to be trucked in weekly, sometimes daily.

Entire communities found themselves rationed. Taps in cities like Marrakech and Agadir ran dry by early evening and showers were timed. In Casablanca, the Ministry of Equipment and Water imposed night-time water cuts, and instructed traditional Hammams to close three days per week, citing “exceptional scarcity.”

In villages without plumbing, women and girls rose at dawn to walk kilometres to communal wells, only to return with plastic jugs half-filled with brackish water. The impact on agriculture, the backbone of rural life in Morocco, was devastating. Wheat harvests withered. Olive yields shrank by half, turning olive oil, once a staple in the country’s households, into a luxury only a few can afford. In the saffron-growing belt near Taliouine, the precious crocus flowers emerged weeks late and in sparse numbers.

Nomadic herders in the High Atlas have lost entire flocks amid the climate crisis. “There’s nothing to feed them. We’ve sold them or watched them die,” said one Amazigh shepherd near Errachidia.

The government’s 2022 emergency drought plan offered subsidies to farmers and built new desalination plants but for many, the help came too late, or not at all. As rural livelihoods withered, some families abandoned the land and moved to cities, adding to the growing number of people living in precarious urban conditions.

In Zagora, an oasis town carved into the dusty plains where the Draa River once flowed freely, life has always orbited around the date palm. Rows of these ancient trees stretch out beneath the watchful gaze of the Jbel Bani mountains. For generations, the rhythm of the town has been dictated by the seasons: dates in autumn, wheat in winter, scorching heat by spring.

Here, water comes from deep wells and traditional khettaras, underground channels dug centuries ago to catch and guide each drop to crops and homes. But in recent years, the wells have started to run dry. Locals speak of sand creeping into their fields, of trees fruiting late or not at all. The river, once a lifeline, now appears only after rare rains, cutting a pale scar through the valley.

“We suffered a lot the last few years. The drought hit us hard,” said Abrani, a farmer in Zagora.

Then came the rain of September 2024 and again in February 2025. Not a gentle drizzle but a sky-splitting deluge that turned dry beds into torrents and alleys into rivers. The town’s fragile infrastructure buckled under the weight of water it was no longer built to receive.

“The rain didn’t help the farmers much, it has made the locals’ life harder. Streets have flooded but the oasis hasn’t got any better,” added the farmer.

In the arid southern regions of Drâa-Tafilalet, Tiznit, and Zagora, rivers reappeared where dry wadis had ruled for years. Zagora, where annual rainfall rarely breached double digits, received over 200 millimetres in two days, more than it often sees in a year.

In Tata, a desert oasis town, floodwaters tore through palm groves and earthen homes. At least 56 houses collapsed, according to the interior ministry. On 30 September, a man’s body was pulled from the swollen river near Tata. Nine days earlier, a bus carrying 29 villagers had vanished into the torrent. At least 18 people died in the incident, officials said.

“We have never witnessed anything like this,” said Aberahman, a displaced resident from Tata. In the surrounding oasis, around 90% of the date palms lay twisted, uprooted, ruined. By late October, women and children still wandered among the ruins, digging for shoes, blankets, cooking pots, and small fragments of their interrupted lives.

This was southern Morocco – Tata, a desert town on the fringe of the Sahara – a place more accustomed to drought than deluge. As the waters rose, so too did a strange chorus of conspiracy theories. In cafés, in WhatsApp groups, on Facebook threads and YouTube channels, the same theory took root: Morocco had made it rain.

The notion isn’t entirely new.

From Hatfield to Al-Ghait: cloud seeding’s conspiracies and politics

In 1915, an American named Charles Hatfield claimed he could summon rain with a secret brew of chemicals and bravado (critics might add here con artistry). He set up shop near San Diego, climbed a tower, and released his concoction into the sky. What followed was chaos: floods, deaths, lawsuits. He insisted he had delivered what he promised.

However, meteorologists at the time (and since) have pointed out that the region was already due for a significant rain event based on natural weather patterns. There’s no scientific evidence that Hatfield’s methods actually worked or caused the floods.

To some, Hatfield was a visionary and early practitioner of weather modification. To others, he was a lucky charlatan riding on coincidence and natural weather patterns.

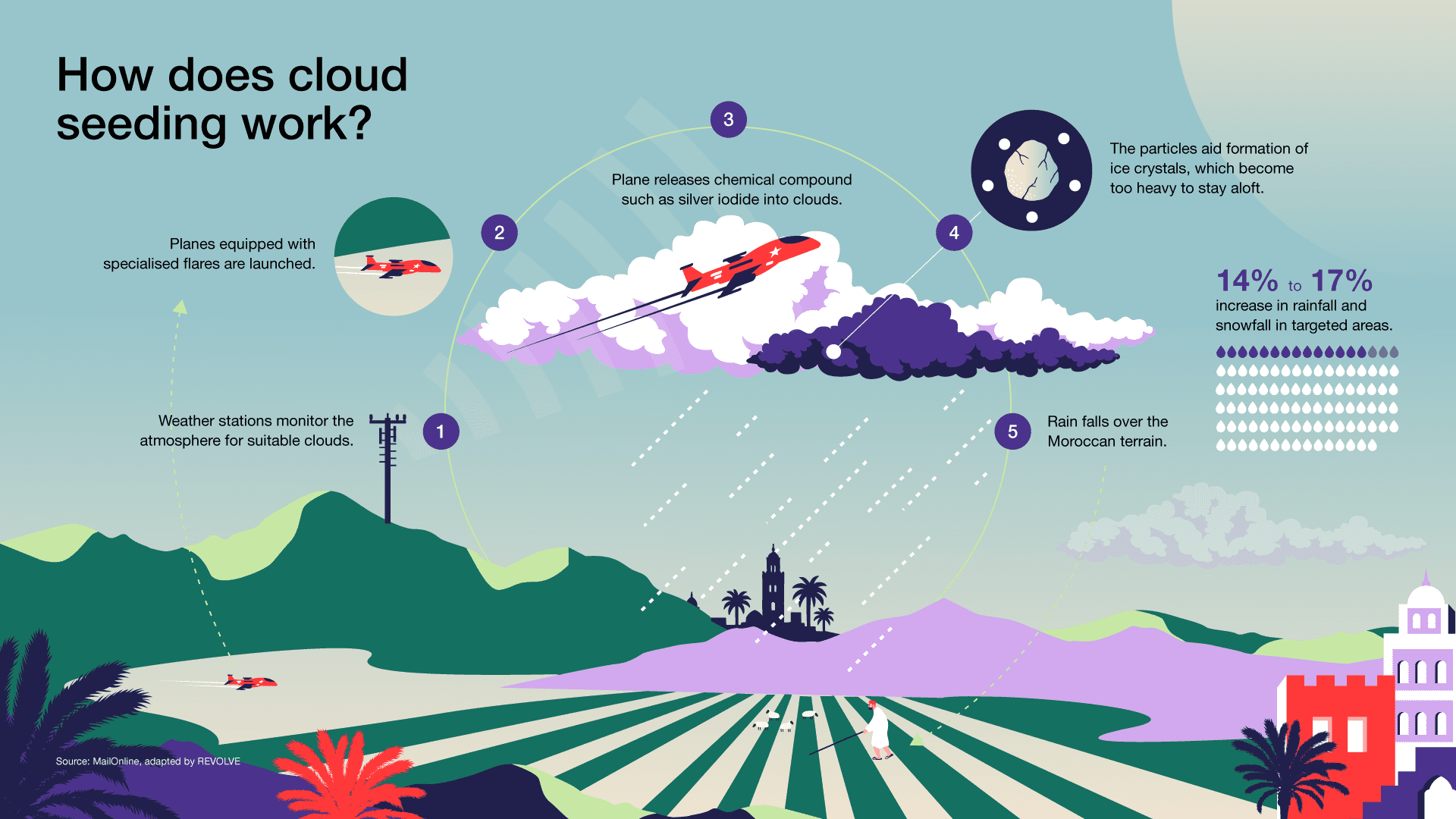

A century later, the methods are more refined but no less controversial. Cloud seeding, the modern iteration of weather modification, involves coaxing moisture from existing clouds. Cloud seeding does not create clouds, nor does it conjure weather out of thin air.

“Oh, it would be great if we could make that much rain,” scoffed Mohamed Jadli, a Moroccan climate expert. “That would solve many problems.”

Simply put, precipitation occurs when water droplets and ice crystals in the clouds, which condense around tiny particles of dust or salt, become too heavy to stay afloat and fall back to Earth with gravity. Cloud seeding artificially stimulates this process by introducing substances into the clouds that simulate the natural process.

Scientists often use silver iodide dispersed from airplanes or ground generators. The substance promotes the creation of ice crystals due to its structure. When it works, the seeded cloud yields a little more rain than it might have otherwise. When it doesn’t, the cloud moves on.

Morocco has been seeding clouds for decades. Between 1984 and 1989, the country partnered with the United States on Programme Al Ghait, a $12 million initiative aimed at boosting water resources. The project equipped Morocco with its first weather radar, trained over a hundred specialists, and tested both airborne and ground-based cloud seeding techniques.

Since 2021, amid an intensifying drought, the Moroccan government has become more vocal about the programme, presenting data in parliament and launching 140 artificial rain operations – 52 by air, 88 from the ground.

“We don’t really know what this rain is. But we aren’t against technology if it’s efficient and it will help.”

Abrani, farmer in the arid plains of Zagora

Yet as floods swept through parts of the country last year, scepticism began to grow. Some Spanish media outlets reported on rising suspicions across the region, particularly in southern Spain and in the Spanish enclaves of Ceuta and Melilla.

“Artificially altering the climate and meteorology can have unpredictable consequences for the entire region,” wrote journalist Pablo Ramos in El Tiempo, a Spanish weather publication. The article also warned that unilateral environmental interventions could provoke geopolitical tension, especially between neighbouring states impacted by cross-border weather events.

Madrid has not formally accused Rabat of triggering the floods.

Still, the idea of weather modification as a geopolitical tool has filtered into the world of online conspiracy, particularly in Algeria, where diplomatic ties with Morocco have long been fraught.

Now, cloud seeding has become the latest subject of speculation on YouTube and in social media circles, where it is portrayed as a covert instrument of influence.

In Rabat, Minister of Equipment and Water Nizar Baraka has tried to calm fears. No cloud seeding, he insisted, had been conducted in the southern regions struck by the severe flood in 2024 and 2025.

The programme, he emphasised, is scientifically guided, activated only during drought and strictly aligned with meteorological data. In March, after another bout of heavy rainfall, I met Dr. Abderrahim Moujane, a meteorologist with Morocco’s General Directorate of Meteorology.

“No, definitely, cloud seeding had nothing to do with the recent rain,” he said, with the air of someone who has fielded this question many times. “We don’t seed when there’s already rain in the forecast.”

Moujane could not give a precise date for the last Al Ghaith operation but was adamant that none had taken place around the time of the floods.

That position was echoed by Omar Baddour, head of climate monitoring and policy services at the World Meteorological Organisation (WMO). The flooding, he confirmed, took place in areas not targeted by cloud seeding and during a period outside the usual operational window.

Still, between official statements and online rumours lies a gulf of uncertainty, where farmers like Abrani, in the arid plains of Zagora, are left to make sense of rains that come too hard, too fast, and droughts that refuse to end.

“So far, despite the recent rain, we’re still struggling with drought,” said the farmer. “We don’t really know what this rain is. But we aren’t against technology if it’s efficient and it will help.”

Cloud seeding: a solution or a problem for Morocco’s weather chaos?

I sought more answers at the Mohammed VI Polytechnic University, a hub for cutting-edge AI research, complex degrees, and students from across Africa seeking specialist qualifications.

Inside its library, I met Perez Kemeni, a researcher at the International Institute of Water Research (IWRI), a newly established research desk in the university. Kemeni spent three years meeting up with farmers, listening to their issues, and engaging in debates with them about agricultural policy.

“What we need is not just more technology – it’s communication. Because right now, the farmers are the ones living with the consequences of both droughts and floods,” he told AMWAJ.

Perez believes that in order to understand the recent drought-flood paradox in Morocco, you have to first understand the country’s complex climate through the eyes of farmers.

The most urgent threat to Morocco’s water resources isn’t just drought. It’s the erratic rhythm of climate change: the unpredictable tempo of rain, the rising heat, and the strain they place on the country’s fragile hydrology.

“What we need is not just more technology – it’s communication. Because right now, the farmers are the ones living with the consequences of both droughts and floods.”

Perez Kemeni, International Institute of Water Research.

For farmers, the story begins, and often ends, with drought. Nearly 80% of them cite it as their main concern, according to the researcher. But drought in Morocco is not simply a matter of dry skies; it’s a cascading chain of climate consequences.

Higher temperatures lead to lower rainfall and faster melting of snowpack in the Atlas Mountains, the natural reservoirs that quietly feed Morocco’s rivers and dams. With warming temperatures, the snow melts too quickly, overwhelming reservoirs briefly before vanishing, leaving dry fields in its wake. This flash of abundance is misleading. Farmers may celebrate after a heavy rain, but that celebration is often short-lived.

Mostafa Salah Benramel, an environmental expert and head of Manarat ecology, an NGO that works with local farmers, elaborated further: “These rains won’t help the farmers much because it came late and inconsistent. Crops require consistency not intensity.”

A wheat plant, for example, needs water during key stages of its growth. Miss the flowering period, and the plant fails to produce grain, regardless of how much water came before or after. Without a steady, predictable supply, the crop’s life cycle collapses.

“The real crisis isn’t that rain never comes. It’s that it no longer comes when needed, and when it does, it often arrives in violent bursts,” explained Kemeni.

Across the Mediterranean and into Morocco, rainfall is becoming more erratic, and more extreme. A single deluge can trigger devastating floods, wash away topsoil, and drown delicate seedlings, only to be followed by weeks of drought.

In late 2024, severe flooding hit Tunisia, Algeria, and Spain, laying bare the region’s deepening vulnerability to climate shocks. In Spain, torrential rains claimed over 230 lives and caused billions in damage. Algeria and Tunisia, too, were overwhelmed by flash floods after rare, violent storms.

Morocco’s clay-heavy soils, while excellent at holding moisture, are poorly suited to these extremes. They flood easily and crack dry just as fast. Hydrologists reported spikes in reservoir levels during the storms, but the gains were fleeting. A brief overflow is little match for a month-long drought.

“It rained,” people will say. But to farmers, that kind of rain is almost meaningless. What they need is the slow, steady drizzle that allows seeds to germinate and fields to breathe.

“These rains won’t help the farmers much because it came late and inconsistent. Crops require consistency not intensity.”

Mostafa Salah Benramel, head of Manarat NGO.

For Kemeni, cloud seeding is promising in theory, yet in practice, it is riddled with complications.

The climate change expert argues that rain induced by human intervention must still align with planting cycles. If it doesn’t, the result can be not just ineffectual, but harmful.

An unexpected downpour in a region with shallow reservoirs or neglected riverbeds can do more damage than good.

Rural farmers need timely, clear information on when and where artificial rain might fall. Without it, seeds are sown too early, or too late. Cropping calendars shift silently, and harvests falter, Kemeni added.

Most Moroccan farmers depend entirely on rainfall for irrigation. If rainfall patterns shift and no one warns them, either through early warning systems or agricultural extension networks, then even the best-intentioned efforts fail.

“Worse, they can become wasteful. Cloud seeding is expensive,” added Kemeni, smiling as he weighed his words. “If it fails to deliver benefits to those who need it most, the cost is not only financial – it is existential.”

For the young researcher, who admits his limited knowledge vis-à-vis the technology, there is a more unsettling question: how much control does cloud seeding really offer? If clouds can be triggered to release rain, can we determine how much falls, or where it lands?

“If not, the country risks solving one crisis by unleashing another,” he said. “Floods can destroy entire harvests. And after that, few farmers can afford to replant. Seeds are expensive. Insurance is rare.”

In Morocco, the question is no longer whether it will rain – but how, when, and at what cost.

Ancestral practices or modern technology?

Moroccan meteorological authorities, as well as the WMO, maintain that cloud seeding is used only when strictly necessary. While the El Ghaith programme reportedly doesn’t directly consult with farmers, it includes climate specialists familiar with the rhythms of the land.

Dr Abderrahim Moujane, a leading forecaster with Morocco’s General Directorate of Meteorology, insists the floods were a result of failing infrastructure, not cloud seeding. The technology, he added, has helped the country withstand prolonged droughts.

Yet even internationally, the promise of cloud seeding is fading. Australia scaled back major programmes in the 2000s after inconclusive results. In the United States, only a handful of states continue using the technology, mostly in mountainous regions. Senegal, once a partner in Morocco’s weather modification efforts, has since retreated, citing inconsistent rainfall outcomes and shifting climate conditions.

Omar Baddour, a senior climate official at the WMO, estimates that cloud seeding can, at best, increase rainfall by 15%, if conditions are favourable. “That is not enough,” he said.

“At the heart of Morocco’s water crisis is a model of agricultural development that has prioritised exports over resilience.”

Abdeljalil Takhim, spokesperson of the local environmental local platform Nechfate.

In parallel, Morocco is scaling up desalination projects, particularly around Casablanca and Agadir. But local groups warn these are stopgap measures.

“At the heart of Morocco’s water crisis is a model of agricultural development that has prioritised exports over resilience,” says Abdeljalil Takhim of Nechfate (a Darija word meaning “it dried”), a local platform focused on raising awareness on climate change issues.

Since the early 2000s, state policy has shifted towards liberalisation, championing high-value crops such as tomatoes and berries for European markets. The 2008 Green Morocco Plan deepened this focus, investing in drip irrigation and genetically improved seeds to boost yields and foreign currency.

But this model has marginalised rain-fed agriculture – the backbone of subsistence farming in Morocco’s mountains and oases. Cereal crops and other staples, once central to food security, have been dismissed as low value.

Even water-saving technologies have had a paradoxical effect: widespread adoption has led to excessive groundwater extraction, draining aquifers faster than they can replenish, according to Nechfate.

“Government subsidies have mostly benefited large agribusinesses, enabling water-intensive practices while leaving smallholder farmers behind,” Takhim said. “And much of the subsidised produce isn’t even consumed locally – it’s shipped to European grocery stores.”

The profits rarely reach the rural communities whose wells are running dry.

What Morocco needs now, Nechfate argues, is a philosophical shift: away from export-oriented agribusiness and toward agroecology and sustainable, locally rooted practices rooted in the knowledge of those who have cultivated these lands for generations.

“Traditional water-sharing systems, drought-resistant crops, smallholder farms, these carry not just genetic diversity, but a legacy of resilience,” Takhim said.

In a country where rainfall is both omen and algorithm, the future may depend on an uneasy partnership: Rabat’s satellites, silent and precise, scanning the upper air; and the mountain farmers, reading the clouds as their ancestors once did.

Between them lies not just distance, but a different way of knowing. Yet for environmental experts, only in that fragile space, Morocco may find its way out of its climate crisis, not by controlling the sky, but by learning to coexist with its caprice.

This article was produced as part of the first edition of the AMWAJ Media Fellowship in 2025. For more information, go to amwaj-alliance.com/media/early-career-journalist-fellowship/