Urban sprawl in a small country like Lebanon poses serious challenges to both the environment and the economy. These challenges manifest in various ways, including the alteration of natural landscapes, the depletion of natural resources, and considerable financial losses, as evidenced by the issue of quarry damage.

Despite its small size, Lebanon is characterised by a rich natural landscape and diverse geography. The Lebanon and Anti-Lebanon mountain ranges run parallel across the country, giving rise to a variety of climates and land formations. The widespread availability of natural materials in the country, such as limestone and sandstone, combined with high demand for construction materials, has driven the growth of the quarrying industry. However, the negative impacts of this industry have been exacerbated by weak regulation and oversight.

Limestone, sandstone, and other sedimentary rocks are among Lebanon’s most abundant natural resources, making the country a significant source of raw materials for the construction sector. The environmental consequences of quarrying have been exacerbated by decades of war and political instability across the Levant, leaving a deep and lasting impact on Lebanon’s ecological and socio-economic fabric.

The quarrying industry in Lebanon is marked by significant fluctuations, often influenced by political and economic developments. Periods of surging demand and heightened production have typically followed major conflicts as reconstruction efforts intensify the need for building materials. For instance, after the end of the civil war in 1990, quarry activity increased dramatically to support nationwide rebuilding.

“A study revealed that between 2007 and 2018, some 1,235 illegal quarries were operating across the country. “

Another major boom occurred in 2000, following the unconditional withdrawal of Israeli occupation forces from South Lebanon, which again spurred extensive construction activity. In the aftermath of such events, demand for raw materials tends to rise rapidly, prompting the swift expansion of quarry operations across the country.

Poor regulation and illegal activity in Lebanon’s quarrying industry

Regulatory frameworks for Lebanon’s quarrying industry were introduced slowly and failed to keep pace with the sector’s rapid and often unregulated expansion. It was not until 2002 that Law 444 (enforced through Decree 8803/2002) was enacted to regulate the establishment, licensing, operation, and rehabilitation of quarries and crushers. A key provision of this law requires quarry operators to submit a site plan, an environmental impact study, a reclamation plan, and bank guarantees. It also outlines criteria for site selection, taking into account proximity to protected natural areas, water resources, and residential zones. While the reclamation plan is a critical component of the application process, it is frequently neglected in practice.

A study titled “Calculating the Quarrying Sector’s Dues to the National Treasury in Lebanon”, published in April 2023 by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and Lebanon’s Ministry of Environment, revealed that between 2007 and 2018, some 1,235 illegal quarries were operating across the country. By 2019, only 10 to 12 of these sites were operating in full compliance with legal and environmental rehabilitation requirements. A subsequent survey conducted by the Lebanese Army in 2023 recorded 1,607 quarry and crusher sites –both licensed and unlicensed –across Lebanon. These figures suggest that only 372 sites were licensed during the 2018-2023 period. According to the latest reports, only one quarry in Lebanon is currently operating with a valid licence.

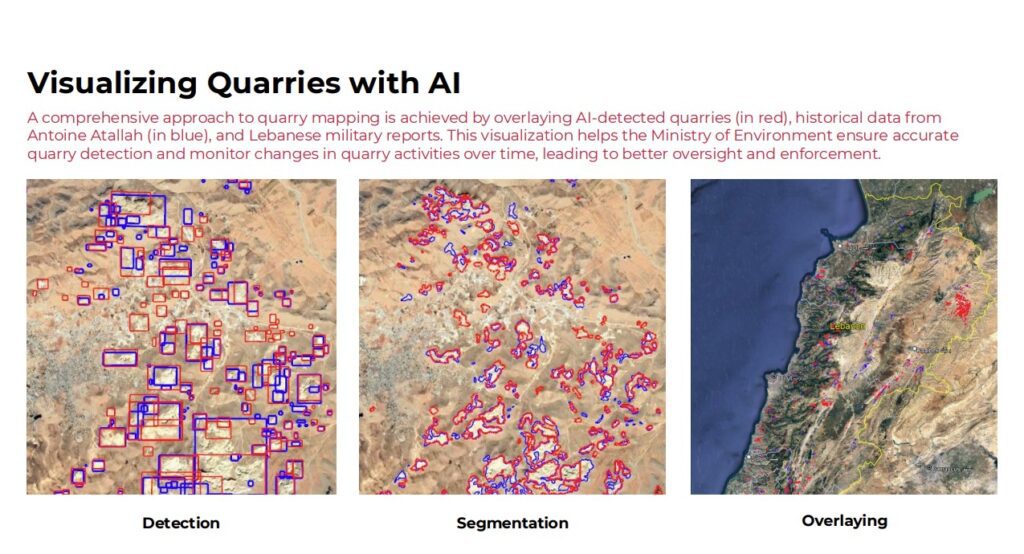

Advancements in artificial intelligence –particularly the use of AI models trained on satellite imagery to detect quarry activity –have revealed far more environmental damage and a significantly higher number of unlicensed quarries than previously estimated. Identifying and monitoring quarries was once a difficult and time-consuming task, especially when it involved surveying vast and often remote areas. AI has now made it possible to efficiently scan large territories, uncovering unauthorised operations that had previously gone unnoticed.

In the infographic above, the areas marked in red represent quarries detected by AI, while those in blue correspond to historic data provided by architect and urban planner Antoine Atallah, as well as the Lebanese Army. The overlay clearly shows that the AI identified a significantly larger number of quarry sites, including many that were previously unknown to the army.

Mismanagement and a lack of oversight have cost the Lebanese government an estimated $2.4 billion in lost royalties and unpaid rehabilitation fees from quarry operations. These losses fall into two main categories: the cost of environmental degradation and the pending rehabilitation costs associated with quarries that failed to comply with legal licensing requirements.

“Mismanagement and a lack of oversight have cost the Lebanese government an estimated $2.4 billion.”

According to a study by Youth4Change, approximately $1.9 billion of this total stems from rehabilitation interventions mandated by the government but not carried out by quarry operators. The large number of illegally operating quarries has made enforcement especially difficult. Moreover, rehabilitation requirements are highly site-specific, necessitating a case-by-case approach based on the unique characteristics and conditions of each location.

Potential rehabilitation and transformation of the quarry

Rehabilitation can involve a range of measures, including recontouring and land shaping, re-vegetation or afforestation, and post-closure land use planning. Under existing legislation, post-closure land use is a mandatory component of the rehabilitation process. This involves transforming the former quarry into a usable space by assessing the site’s size, depth, slope stability, water table level, and any contamination, followed by defining its future use. Potential outcomes include public parks, agricultural fields, artificial lakes, or reshaped terrains that integrate into the surrounding landscape.

In Lebanon, an example of successful quarry rehabilitation is the Holcim Quarry Rehabilitation Project in the northern town of Chekka. The project saw approximately 132,000 m² of former quarry land restored through the construction of terraces and water ponds, which helped to stabilise the terrain. This was followed by the planting of over 3,000 native shrubs and trees, including species such as olive, oak, and thyme. Such interventions not only help prevent future erosion but also contribute to the restoration of local flora and fauna, supporting long-term ecological balance in the area.

The Way Forward

The notion of implementing the Chekka success stories across all of Lebanon’s quarries and pairing it with a functioning system of accountability and responsibility might seem daunting, but there are numerous protocols and tools that can be introduced to make the industry more sustainable and better regulated.

Given the large number of abandoned and unrehabilitated quarries across Lebanon, it is essential to develop clear prioritisation criteria to determine which sites require immediate intervention and which are less urgent. These criteria should consider the quarry’s proximity to residential areas, its potential for ecological or structural restoration, the presence of plant and animal species –particularly those that are endangered or vulnerable –, the site’s history of legal compliance with environmental regulations, the existence of any ongoing illegal extraction activities, and the length of time the site has been abandoned.

At the administrative level, digitising data and automating regulatory processes would significantly improve efficiency and compliance. As the legal framework is often complex and difficult to navigate, the development of a user-friendly digital platform could help simplify procedures and provide access to up-to-date legal and environmental information, while offering a space for public enquiries.

Ensuring compliance with quarrying regulations requires coordinated enforcement by several key institutions. The Ministry of Environment is responsible for developing laws and regulations to address existing challenges and oversee environmental compliance. The Internal Security Forces play a critical role in identifying and reporting violations on the ground. Meanwhile, the Judiciary is tasked with applying penalties and pursuing legal action in cases of non-compliance.

This article was developed as part of the Climate Change and Environmental Justice Training Series organised by AMWAJ in partnership with the Heinrich Böll Foundation Middle East.