As the impacts of climate change become more visible, drought across the Mediterranean region is no longer the exception – it’s becoming the rule. Southern Europe and North Africa are experiencing severe water stress due to declining rainfall and rising temperatures, as well as increasing demand from irrigated agriculture, tourism, energy, and urban growth. In this shifting climate, Spain stands out as both a high-risk zone and a testing ground for solutions, offering lessons for the wider region. Faced with mounting water scarcity, Spain has increasingly relied on alternative water sources like desalinated and reclaimed water, which have become strategic resources for guaranteeing supply and building long-term resilience.

Would you be willing to drink reclaimed water during periods of water scarcity? How about consuming food grown with this resource? Would your perception change if it were desalinated water instead? And what if this were the only water source available?

These are no longer theoretical questions. In regions like the Canary Islands and along the Mediterranean coast, desalinated water already forms part of the public supply, while reclaimed water is extensively used in agriculture in southeastern Spain. Catalonia, severely affected by drought, has even implemented indirect potable reuse by integrating reclaimed water into the Llobregat River basin for urban consumption.

These approaches are already transforming how water is managed in regions where traditional supplies are no longer sufficient, but their long-term success will also depend on how they are understood and accepted by society.

To explore this social dimension, Elcano Royal Institute, one of the leading Spanish think tanks, conducted a survey between February and March 2025, polling 1,400 individuals across six Spanish regions with different water contexts: Andalusia, Catalonia, Galicia, Madrid, Murcia, and Valencia.

What does the Spanish public think?

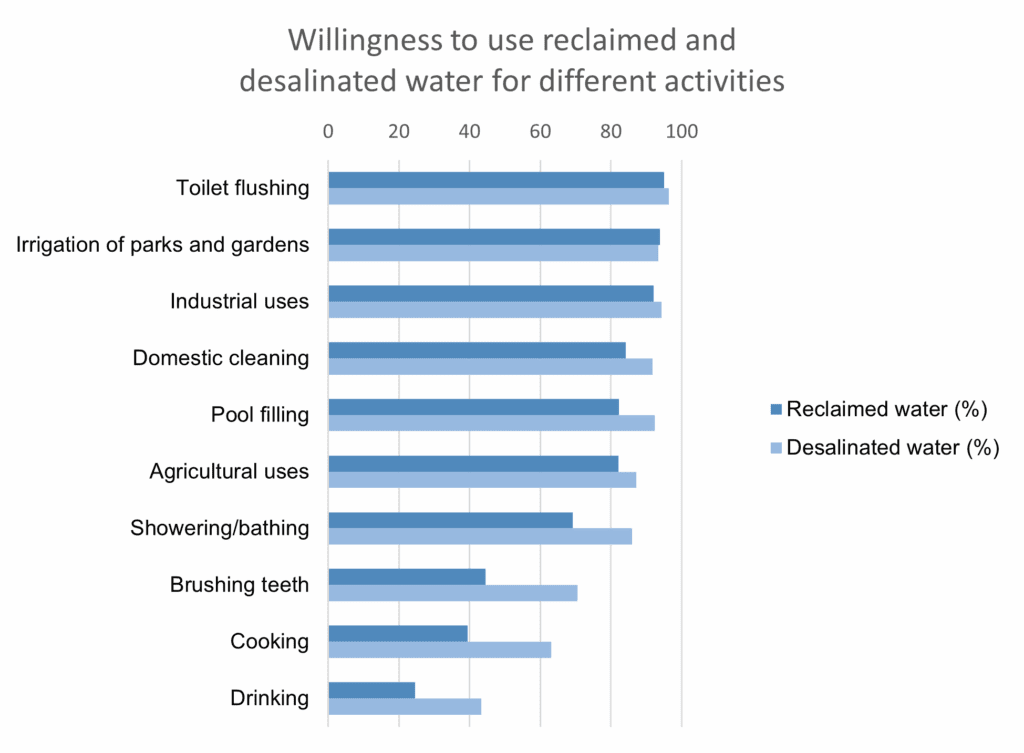

Survey results indicate high willingness to use reclaimed and desalinated water resources for toilet flushing, watering parks and gardens, agricultural and industrial purposes, or filling swimming pools, with acceptance rates exceeding 80% in all cases. Willingness sharply decreases for domestic uses involving direct human consumption, particularly for reclaimed water: only 39% would accept it for cooking and 25% for drinking. For desalinated water, acceptance rises to 63% and 43%, respectively.

This openness towards unconventional water resources aligns with strong normative support, surpassing alternative policies aimed at increasing water supply, such as reservoir construction or interregional water transfers, as well as demand management measures like price increases or reduced irrigation water allocations.

The reuse of reclaimed water receives the highest public backing at 84%, peaking in Madrid (89%) while it is lowest in Galicia (79%). Support increases in line with income and educational levels, reaching 97% among students.

The construction and/or expansion of desalination plants also enjoys broad public support, with agreement levels above 70% across most demographic groups surveyed. Support is particularly high in Andalusia and Catalonia (76%), and lower in Galicia (65%). Income level remains a key factor: backing rises among higher-income groups, reaching 82%. Additionally, men show a higher level of support (74%) than women, and acceptance drops among those with lower educational attainment (67% among individuals with only compulsory education).

Who’s Willing to Drink Reclaimed or Desalinated Water—And Why?

Although Spanish citizens express strong concern about water-related issues, particularly in drought-prone regions, this concern does not always translate into active acceptance of these options, especially for sensitive uses like human consumption. The Elcano survey data sheds light on the variables that explain or limit public willingness using statistical data to assess the effects of several socio-demographic, behavioural, and ideological factors.

The most relevant predictor of willingness to drink one type of unconventional water was acceptance of the other: willingness to consume desalinated water increased acceptance of reclaimed water by 31%, and vice versa by 40%, indicating resistance ties more to the idea of unconventional water than to specific technologies, according to the survey results.

Social interactions distinctly impact acceptance: discussing reclaimed water reduces willingness by 5%, possibly because it reinforces concerns about health risks or water quality. In contrast, conversations about desalinated water appear to have the opposite effect, increasing acceptance by 6%, likely due to greater familiarity or positive peer influence.

Ideological and demographic factors influence acceptance differently. Left-leaning and younger individuals show higher acceptance of reclaimed water, while willingness to pay extra on the water bill to ensure supply, gender, and geography notably affect acceptance of desalinated water. Residing in the Mediterranean Arc was associated with a 7% lower likelihood of accepting these resources, despite the region being where such technologies are most widely implemented. This relative reluctance may be influenced by factors such as mistrust in water quality, negative taste perceptions, or a greater reliance on bottled water.

Other variables analysed such as living in water-stressed areas, institutional trust, habitat size, education level, or income did not prove to be decisive in determining acceptance of these resources.

Trust and communication: keys to accepting unconventional water

The main barrier identified in the survey regarding the use of reclaimed and desalinated water is distrust in the quality of the resource: 64% in the case of reclaimed water and 48% for desalinated water. This perception appears to be influenced by low levels of trust in institutions and water sector companies, despite the fact that current technologies provide highly effective treatments adapted to the intended use and fully comply with the highest quality standards under current regulations.

Additional concerns include hygiene, health risks (19%), unpleasant taste (12%), and psychological aversion, often termed the “yuck factor” (8%) for reclaimed water, while desalinated water faces issues related to taste (25%), high cost (11%), and energy consumption (10%).

Addressing these barriers requires fostering trust and social legitimacy through transparent communication, showcasing successful case studies, active public participation, and targeted educational campaigns. Singapore’s NEWater initiative remains a global benchmark for successful acceptance through strategic communication and education.

As climate change intensifies drought and water scarcity across the Mediterranean, the transition to resilient water systems is no longer optional –it is essential. Countries throughout the region, such as Spain, Cyprus, Morocco, and Tunisia, are increasingly investing in reclaimed and desalinated water. These investments in innovation must be accompanied by efforts to build public trust, strengthen inclusive governance, and foster knowledge sharing across the region.

The Mediterranean’s collective experience highlights that adapting to scarcity is not merely a technical challenge; it is a social and political one. Spain illustrates this reality clearly. While the country leads in reuse and desalination, water governance still faces a structural challenge that extends beyond technology or financing: it requires public legitimacy.

Moving forward, achieving a water-secure Mediterranean will demand more than pipes and plants. It will require a cultural shift toward shared responsibility, institutional trust and long-term resilience. Technological solutions must be supported by an informed and engaged public. A drop reclaimed or desalinated in one country may inspire progress across the region. But lasting water resilience in the Mediterranean will depend on something harder to engineer: citizens’ trust.