From the Treaty of Lausanne to the Shatt al-Arab, from the Bada’a Canal to desalination projects, Basra has a long and winding history of water struggles. A city once imagined as Iraq’s richest in water has become one of its thirstiest, saltiest, and most marginalised.

Since the founding of the modern Iraqi state in the early 1920s, the country has faced a serious challenge: water scarcity, which has resulted in disputes with its three neighboring countries. The conflict with its northern neighbor, Türkiye, over Iraq’s share of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers began shortly after the collapse of the Ottoman Empire and the establishment of Iraq. Türkiye has long relied on Article 109 of the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne to avoid signing any binding agreement with Iraq or Syria regarding water sharing. This Article entrusted the concerned countries with the responsibility of reaching an agreement to protect their respective interests and acquired rights. In cases where no agreement could be reached, the matter was to be settled through international arbitration.

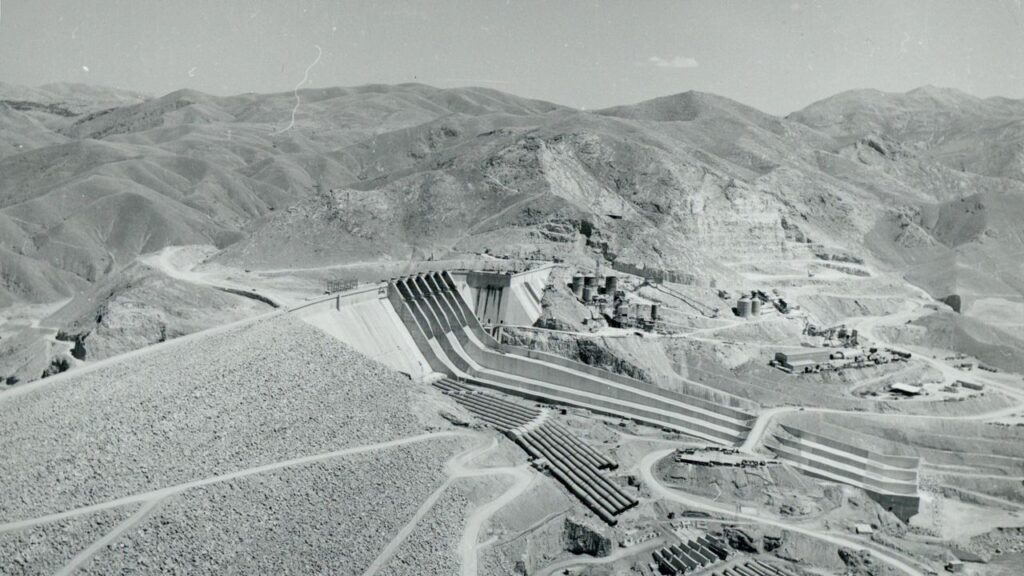

Despite the signing of the Friendship and Good Neighbourliness Treaty in 1946 between Iraq and Türkiye –which included provisions related to water, Ankara did not adhere to the agreement’s terms regarding water management. Instead, it continued its evasion, procrastination, and delays. In 1966, Türkiye began construction of the Keban Dam, which was officially inaugurated in 1974. The project immediately raised concerns in Iraq, especially following the announcement of the dam’s reservoir filling. The Keban Dam, one of the most significant dams on the Euphrates River in Türkiye, stands 207 metres tall and has a storage capacity of 30.6 billion cubic metres.

Türkiye took advantage of the Iran-Iraq War, which began on 22 September 1980, and ended on 8 August 1988, as well as of Iraq’s preoccupation with the conflict, to launch the Southeastern Anatolia Project (GAP) in the mid-1980s. This project involved the construction of several dams and tunnels along the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, as well as irrigation canals and numerous hydroelectric power stations.

The long water dispute between Iran and Iraq

In parallel to the water dispute between Türkiye and Iraq, a separate conflict over water also existed between Iraq and Iran. This dispute originated from Tehran’s demand, after Baghdad’s independence, to share sovereignty over the Shatt al-Arab. The first formal agreement between the two countries was the 1937 treaty, under which Iran recognised Iraq’s sovereignty over both banks of the Shatt al-Arab except for certain areas on the eastern bank, which were placed under Iranian sovereignty.

However, the situation changed. Following the fall of the monarchy and the establishment of a republican regime in Iraq, Iran promptly called for a redrawing of the Shatt al-Arab border based on the thalweg line (the deepest point of the river channel as the boundary). This significantly strained relations between the two countries. In response, Iraqi Prime Minister Abdul Karim Qasim demanded sovereignty over Iran’s Khuzestan province – then commonly referred to by some Arab nationalists as “Arabistan”– which lay along the eastern bank of the Shatt al-Arab. This sparked a series of skirmishes between the two sides, although the tensions stopped short of escalating into a full-scale war.

In its effort to assert sovereignty over the eastern bank of the Shatt al-Arab, Iran provided logistical support to Kurdish forces opposed to the ruling regime in Baghdad during the armed conflict in northern Iraq, which lasted from 1961 to 1969. In 1969, Iran unilaterally annulled the 1937 treaty, and soon after mobilised various branches of its armed forces along the border with Iraq in anticipation of a possible response. However, the Iraqi regime – still in its early stages and led by the Arab Socialist Ba’ath Party – did not retaliate militarily. Instead, Iraq shifted its strategic focus to the port of Umm Qasr, which had been inaugurated in 1964, as its primary outlet to the Gulf. This move was later reinforced by the opening of the Khor al-Zubair port in 1974.

As part of its continued pressure on Iraq, Iran once again provided logistical support to Kurdish forces during their second armed conflict with the Iraqi regime, which began on 16 April 1974. This support ultimately enabled Iran to compel Iraq to accept its demands, leading to the signing of the Algiers Agreement on 6 March 1975. Under the terms of the agreement, Iraq ceded control of half of the Shatt al-Arab to Iran in exchange for an end to Iranian support for the Kurdish insurgency. As a result, the Kurdish-Iraqi conflict came to an end shortly thereafter, on 25 March 1975.

By October 1977, protests against the Shah of Iran, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, had begun to spread across Iran. These demonstrations were followed by the Islamic Revolution in Iran, which started on January 7, 1978. The revolution ultimately led to the fall of the Shah on 11 February 1979, and the establishment of the Islamic Republic of Iran under the leadership of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini.

Approximately five months after the establishment of the Islamic Republic in Iran, a major political event occurred in Iraq. On 16 July 1979, Saddam Hussein assumed the presidency, succeeding Ahmed Hassan al-Bakr. Relations between Iran and Iraq quickly deteriorated, resulting in the declaration of war between the two sides on September 22, 1980.

During the Shah’s rule and under the current regime, Iran constructed numerous dams on the Karun River and on tributaries of the Tigris River, significantly reducing Iraq’s share of water. In an effort to destroy the agricultural sector in Iraq, and after the fall of Saddam’s regime in April 2003, Iran adopted a different but equally damaging tactic: economic market flooding. It was based on exporting vast quantities of Iranian goods into Iraq at prices below production cost. The goal was to dominate Iraqi markets, undercut local products, and render domestic competition unviable. As a result, Iraqi farmers and industrialists suffered severe financial losses, leading many to abandon their work. This contributed to the collapse of both the agricultural and industrial sectors, giving Iran significant influence over Iraq’s economy and, by extension, over its political decision-making.

A similar situation unfolded in Syria, which constructed several dams on the Euphrates River, the most important being the Euphrates Dam, the Baath Dam, and the Tishrin Dam. This development led to recurring tensions between Iraq and Syria, largely due to the reduction in the flow of Euphrates River water entering Iraq through Syrian territory.

The water policies adopted by Iraq’s three neighbouring countries can be described as a de facto water war against Iraq. These arbitrary policies drastically reduced Iraq’s share of transboundary waters. It resulted in Iraq losing vast areas of water bodies and agricultural lands, while desertification rates accelerated. Agricultural and livestock production declined sharply, leading to an imbalance in the demographic structure. Farmers and herders migrated from rural areas to urban centres. Rising temperatures, increasing pollution levels, the spread of diseases, and water scarcity further deepened the crisis.

Basra’s water crisis

Basra Governorate was the most prominent – and the most affected – Iraqi region to suffer from the arbitrary water policies pursued by Iraq’s three neighboring countries over the past decades, because it is located at the southernmost tip of Iraq, where the Tigris and Euphrates rivers converge. The crisis of access to potable water in Basra began with the outbreak of the Iran-Iraq War on 22 September 1980. During the conflict, numerous water filtration and pumping stations, transmission lines, and distribution networks were severely damaged by Iranian airstrikes. In addition, the waters of the Shatt al-Arab, along with its branching rivers – then the primary source of raw water for most of these facilities – became heavily polluted, due to the leakage of large quantities of fuel and oil from ships docked in the waterway at the time, many of which had been struck and damaged by Iranian bombing. Additionally, routine dredging operations in the Shatt al-Arab were suspended due to the ongoing war.

Although the water treatment and pumping stations, transmission lines, and distribution networks were rebuilt shortly after being damaged by the bombings, they remained unable to treat the high levels of oil and industrial pollutants that contaminated the waters of the Shatt al-Arab and its tributaries.

With no alternative water source besides the polluted river water, most residents of Basra were forced to use tap water for washing, cooking and drinking, despite its unsuitability. This resulted in the spread of skin, intestinal, and kidney diseases. The wealthier segments of the population turned to bottled water for drinking purposes, which began to appear in limited quantities in local markets by the mid-1980s. The situation continued as it was, from bad to worse, with no viable solution in sight as the war between Iraq and Iran dragged on.

After the war ended with a ceasefire on 8 August 1988 – following UN Security Council Resolution No. 598 of 1987– hope was rekindled among the residents of Basra for a solution to the water crisis, as the crisis had become a serious threat to their health and livelihoods. However, that hope quickly faded away. As part of the major reconstruction campaign launched immediately after the ceasefire, state institutions opened sewage lines into the Shatt al-Arab and its tributaries. This resulted in most of the rivers branching off from the Shatt al-Arab, particularly those running through the city centre, were transformed into stagnant waterways.

The severity of the water crisis in Basra worsened following Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait on 2 August 1990, and the imposition of economic sanctions on Iraq under UN Security Council Resolution No. 661 on 6 August 1990. The sanctions had far-reaching effects across Iraq. One of the most significant ones was the country’s inability to import the equipment, spare parts, and chemicals needed to operate water filtration and pumping stations, as well as sewage treatment plants, in all governorates. As a result, these stations began dumping their waste into rivers, ultimately flowing into the Shatt al-Arab, which lies at the confluence of the Tigris and Euphrates.

To mitigate the impact of the water crisis on the people of Basra, the government installed concrete water tanks with capacities ranging from 2,000 to 2,500 litres in several neighborhoods, particularly working-class and rural areas. These tanks were regularly filled with fresh water delivered by tanker trucks, which transported water from two desalination plants, operated by the General Company for Paper Industries and the General Company for Petrochemical Industries in Basra. Residents were allowed to collect fresh water from these tanks free of charge, using plastic containers and various household utensils, while waiting for the inauguration of the Al-Nabaa Al-Safi water treatment station.

The Al-Safi Spring Station is a private facility built at the time by a local businessman. It received raw water transported by tanker trucks from the Gharraf River, located north of the city of Nasiriyah. The station filtered the water to remove suspended particles and silt. It was then purified for consumption. The treated water was sold directly to residents at the station or distributed through a network of agents stationed across various districts and neighborhoods of Basra. These agents were supplied with fresh water from the station using tanker trucks.

Due to the obstacles that hindered the lifting of the economic sanctions imposed on Iraq under the aforementioned UN Security Council resolution, and in light of the worsening crisis in Basra and its severe repercussions, the government at the time found itself compelled to launch the “Loyalty to the Leader” project– now known as the Al-Bid’a Canal Project.

The Al-Bid’ah Canal is an open, artificial waterway with a total length of 238.5 kilometres. Of this, 144 kilometres are lined with concrete, while the remaining 94.5 kilometres are lined with selected, slightly saline clay soil. The canal transports water from the Gharraf River, located on the outskirts of the Shatrah District in the north of Dhi Qar Governorate, to the cities of Nasiriyah, Suq Ash-Shuyukh, and Basra. Some 70 % of the canal lies within the administrative borders of Dhi Qar Governorate, while the remaining 30% runs through Basra Governorate.

When the Al-Bid’ah Canal project was launched in 1997, fresh water began reaching all areas of central Basra Governorate, as well as the district centres of Al-Zubair, Shatt al-Arab, Abu Al-Khaseeb, and Al-Faw. However, other areas continued to rely on older sources to obtain raw water for treatment facilities. Meanwhile, the northern regions of Basra continued to depend on the upper Shatt al-Arab, along with the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, as their primary sources of raw water.

Immediately after the inauguration of the Al-Bid’ah Canal project, the Ministry of Irrigation issued circulars prohibiting the use of Shatt al-Arab water for irrigation purposes. However, despite the arrival of fresh water to the residents of the aforementioned areas, most people refrained from using it for drinking or cooking, due to concerns over contamination as it passed through the deteriorating distribution networks. Instead, they continued to purchase water deemed safe for human consumption.

No lasting solutions to Basra’s water crisis after the fall of Saddam Hussein

The situation remained unchanged until the fall of Saddam Hussein’s regime on 9 April 2003, marking the beginning of a new phase of suffering for the people of Basra. Following the regime’s collapse, the province experienced a sharp rise in population density –driven by increased birth rates, the return of tens of thousands of residents who had migrated to Iran and other countries during Saddam’s rule, and the influx of hundreds of thousands of people displaced from other Iraqi governorates for various reasons. This led to the emergence of dozens of new residential neighborhoods, the destruction and fragmentation of tens of thousands of hectares of agricultural land converted into housing, and the spread of informal settlements.

These developments were accompanied by serious and widespread violations of water supply networks, the establishment of numerous government departments and institutions, the construction of educational and commercial facilities, entertainment and tourist complexes, industrial and agricultural installations, poultry farms, and other projects –along with the arrival of hundreds of thousands of Arab and foreign workers –which all contributed to a significant surge in demand for water.

However, in response to the surge in demand, the relevant authorities failed to take the situation seriously. They were forced to reactivate most of the water filtration and pumping stations, relying once again on the waters of the Shatt al-Arab to meet the population’s immediate needs. At the same time, pollution levels and salinity concentrations in the Shatt al-Arab increased significantly due to the reduced flow of water from the Tigris River through the Qala Salih Regulator, as a direct result of the water policies adopted by neighbouring countries, which– as previously mentioned– led to a sharp reduction in Iraq’s share of water resources.

Some donor countries and international organisations took the initiative to support Iraq in addressing the potable water crisis in Basra by providing financial grants to rehabilitate and upgrade existing water purification and sterilization projects. Others donated dozens of water purification and desalination plants with small to medium production capacities, intending for them to be installed, operated, and used to alleviate the burden on residents. However, the vast majority of these plants proved ineffective due to their limited output, which was insufficient to meet the needs of a small village in Basra. As a result, many remained stored in warehouses or left outside until they eventually deteriorated. A few medium-capacity plants were installed and leased by the Basra Water Directorate to the private sector, which operated them and sold the treated water to residents.

The United States of America was among the countries that donated tens of millions of dollars to support the rehabilitation and development of several water projects in Iraq. This included a $25 million contribution to implement three major water projects, each consisting of a large underground concrete reservoir and an elevated tank, supplied by the Abbas Water Project, which is itself fed by the Al-Bid’a Canal. The objective was to provide the Al-Hussein neighborhood and its surrounding areas with water suitable for human use. However, despite being completed over 14 years ago, these projects have yet to become operational due to a lack of prior coordination between the American and Iraqi sides. As a result, all three projects have fallen into disrepair. Recently, UNICEF has undertaken their phased rehabilitation.

Some countries have also taken the initiative to offer financial loans to Iraq aimed at implementing major water desalination projects in Basra to help address the ongoing crisis. Among these countries is Japan, which provided a loan to finance the large Basra Water Project in Al-Hartha, located north of Basra Governorate’s centre. The project consists of four phases: while the third and fourth phases have been completed, the first and second phases remain under construction despite more than a decade having passed since the project’s launch.

The United Kingdom provided a loan to finance a seawater desalination project in Basra, with a planned production capacity of one million cubic metres of potable water per day. Although a bilateral agreement was signed between the two parties in 2017, the implementation contract has yet to be signed. Ultimately, the British companies involved in lengthy rounds of negotiations with the Iraqi side withdrew from the project after concluding that Iraqi officials were not serious about moving forward and were demanding substantial financial commissions prior to awarding the project and signing implementation contracts.

Poor planning and mismanagement, coupled with widespread financial and administrative corruption, have played a major role in the failure to find lasting solutions to Basra’s water crisis. Hundreds of billions of Iraqi dinars have been spent on maintaining and rehabilitating deteriorating water infrastructure, including filtration stations, transmission lines, and distribution networks, as well as on implementing new projects without thorough evaluation. As a result, the situation has continued to deteriorate, with no real or sustainable solution achieved.

The article was first published in Arabic on Jummar on 6 May 2025.

Translated by Mariam Younes